Lead poisoning has been in the news in recent years. In Flint, Michigan, and east of Chicago, Indiana, contamination of water and soil has exposed tens of thousands of people, including children, to disturbing concentrations of lead. These cities are not alone. More than a million children go to school in public schools in New York City and a large number of them have a high and dangerous blood lead level, defined as more than 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood. Contamination of soil and water can be an important source of lead in New York and other environments.

People can be exposed to lead through water, household dust, paint, food and cigarette smoke, and in some industrial jobs. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention it is known that the exposure of children to lead increases the risk of developmental delay, intellectual disabilities, behavioral problems, hearing and speech problems.

Unless removed, lead presents a health risk to the urban population, especially to children and to the gardening population, in the foreseeable future.

Here’s what you need to know about this research and what you can do to protect yourself now from the dangers of lead.

What Have We Learned About Lead Contamination in Soil?

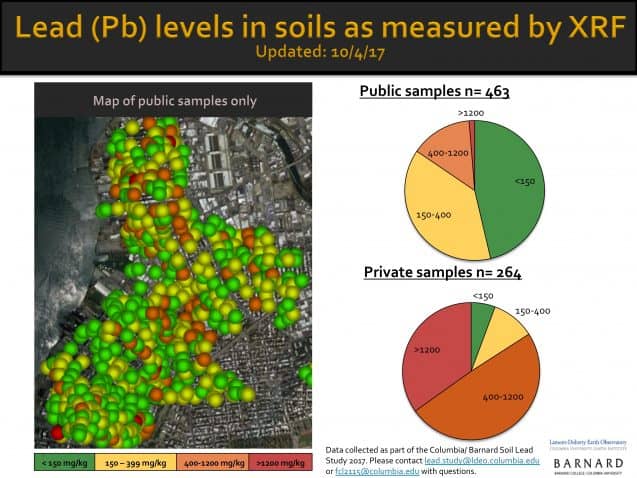

Philip is one of the dozens of the people in Brooklyn who volunteered to have their soil tested by Franziska Landes, a graduate student in Columbia’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. Since this spring, Landes and her team have analyzed 264 soil samples from 52 private backyards. They are still collecting data, but the preliminary results are worrying: about 92% of Greenpoint’s backyards have at least one sample above the level of lead that the EPA has designated as safe for residential soils. Some yards contain seven or eight times more lead than they should, more than the levels observed in some polluted Peruvian mining communities, studied by Landes.

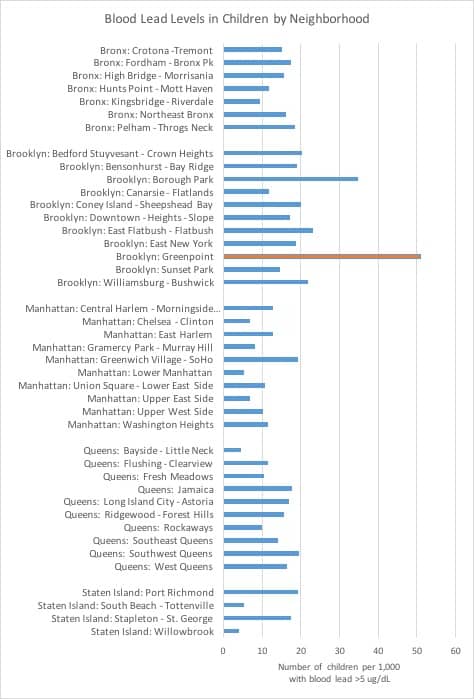

The Percent of the Children in Greenpoint

Whether they are connected to contaminated soil or not, the Greenpoint children are about four times more likely to have lead poisoning than their peers in other parts of New York City. Five percent of the children in Greenpoint have a lead level of more than five micrograms per deciliter of blood, the level at which CDC recommends taking action.

“You like to know what you’re living with,” said Stephanie, another Greenpoint resident who was getting her soil tested that day. To protect their privacy (and potentially the values of their and their neighbors’ homes), Stephanie and Philip preferred not to use their last names.

Digging for an Explanation

Landes and her assistant, Sabina Gilioli, worked efficiently and expanded to Philip’s yard to choose areas to sample and install vials on his patio table. In five places (including the far left corner, bare, except for a dead magnolia), they picked up the dirt with metal spoons and used a colander sieve, sifted larger bunches, they channeled it into the bottles. Each container is carefully labeled; Back in the laboratory they discovered the amount of toxic metal in each of them.

Lead isn’t good for anyone, but it poses as one of the biggest threat for children under the age of six. A neurotoxin, it disturbs the growth of young brains, increasing the risk of developing a low IQ, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and behavioral problems.

Many of the participants in Landes’ study are concerned parents, found through a local activist group called Neighbors Allied for Good Growth. “A lot of times the parents tell us ‘my children have tested high with lead, and that’s why we found this program,’” said Gilioli.

“That’s why we wanted to focus on this area,” explained Landes. “Maybe we could figure out what’s playing a role in this.”

Charted the Lead Levels in Greenpoint Soil

Up to now, nobody had systematically charted lead levels in Greenpoint soil. Brooklyn College will test soil samples that anyone in the United States can mail in, but their data is not always evenly distributed. With a more complete map, Landes hope to conduct distribution surveys to a smaller scale and learn about the relationship between the levels of the yard and the public; for example, are backyard soils more contaminated with lead than in areas where the public soil is not?

“Backyards are often not tested for lead in soils, but they could be harboring high levels of contamination that kids could be exposed to,” said Landes. “Are we missing a potentially large exposure because we’re not looking in the right places?”

Her map is filled with red, green and yellow pins from the samples they’ve collected, many with the help of Barnard environmental scientist Brian Mailloux and his students. But there seems to be no specific motive for the colors on the card. “There is no hotspot,” said Landes. “One of the challenges of working in an urban environment is that there are many potential sources of contamination.”

Lead paint, used until the 1970s, could easily end up in the backyard of people during routine maintenance and remodeling- such as scraping paint off of your front railing, like Philip when we met him. Before leaded gasoline was officially shut down in the 1990s, fine lead particles from exhaust gases rained down in areas with high traffic and close quarters of taxiways. Incineration of waste sent lead particles on a comparable path. In addition, Greenpoint has an industrial history, including the main smelters of the Non-Ferrous Processing Corporation.

“Soils are recording this history, because lead doesn’t go away,” Landes said. Once it’s deposited, lead tends to stick around, not moving much except when it’s kicked up as dust. Vegetables growing in lead-contaminated soil may take up small amounts of the metal, and sometimes lead-contaminated dust gets tracked into the home. But its main route into the human body is through direct ingestion. “Kids are really the concern there,” said Landes. “They like to play in the dirt and then stick their toys in their mouth or suck their thumbs, and they’re not always washing their hands in between.”

A Private Problem

After they have collected the small bottles of soil, Landes and Sabina brought them back to the laboratory to see what they contain. There, they place a plastic film on the opening of each bottle and place it upside down in a metal box that closes like a backyard grill.

From below, an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer gun emits X-rays in the sample. The rays generate electrons in the soil, causing some to jump to an outer layer of the atoms in which they reside. In response, another electron from the outer layer falls into place in the innermost layer, releasing a specific amount of energy that reveals the identity of its atom. By measuring these electron emissions per second, the system calculates the amount of lead and other metals in the soil. It spits the results on a computer screen in less than 60 seconds.

The Environmental Protection Agency sets 400 parts per million as an acceptable level of lead in bare residential soil. The limit is meant for guidance—it’s not enforceable—and there may be risk at levels as low as 100 ppm. So far, Landes and her team have found that some 84 percent of Greenpoint of the backyard samples exceed the EPA standard, and 35 percent have lead levels over 1200 ppm, the EPA’s standard for industrial soils. Of the 52 yards sampled, 33 (that’s 62 percent) had at least one sample that exceeded the industrial standard, and a few have gone as high as 3,000 ppm. “Even as an adult I wouldn’t want to be hanging out in those yards,” said Landes.

On the other hand, only about 14% of the 463 samples collected by the team in the public parks and sidewalks exceed the lead levels. Landes doesn’t know why the lead contamination is so much higher in private spaces, but this may have to do with the proximity of the rotting paint from the house and the remains of burnt garbage. In addition, only older soil is inherited from leaded gasoline, waste incineration and industrial by-products; public space is more likely to receive new soil and mulch imported elsewhere for landscaping.

Advisor Van Geen Observation

The work underlines a pattern that researchers at Brooklyn College uncovered in 2015, said Landes’ thesis advisor, Alexander van Geen from Columbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. Those researchers also found high lead levels to be much more common in private yards. “Franziska’s work over the summer really made the contrast between soil in public and private spaces even starker,” said van Geen.

And whilst data suggests that the lead levels in the soil may be related to higher blood lead levels in Greenpoint’s children, the team has not yet proven it. Once samples of Greenpoint have been taken, they must replicate the study in a region where the lead content in the blood of children is particularly low. “If soil lead is low there, too, it will add to the argument that soil contributes in North Brooklyn,” said van Geen. “If it isn’t, then we’re still missing a big piece of the puzzle.”

Taking it to the Streets (and Mines)

One thing that Landes has learned while making her maps is that it’s hard to predict where the lead will be. “You have to test it to find out where the contamination is, and that’s one of the reasons I’m developing a field test.”

Before digging and raising her eyebrows on the sidewalks of Greenpoint, Landes worked in Peru to help mining communities find lead in their soil. Because these rural communities do not have access to expensive analytical equipment, Landes had to design a relatively simple test that works everywhere.

With the help of Landes, the participants mix the soil of their yard with a solution of glycine and hydrochloric acid, shake them, filter them and add a substance that changes color called sodium rhodizonate. At the end, a bright yellow or bright yellow solution indicates low lead levels. Dark yellow means average amounts of lead, and brown to black indicates a high risk.

In Peru, “mothers used the field kit to find areas of contamination that we had missed,” said Landes. In fact, the most difficult thing for them was using a smartphone touchscreen for an app that records the sample’s location and soil properties.

In contrast to the X-ray fluorescence gun, which indicates the total amount of lead in a soil sample, the field test, because it simulates gastric acid and digestive movements, gives a better idea of the amount of absorption of a human body by a sample. Landes strives to increase the sensitivity of the test to improve accuracy with lower lead levels. she purpose is to make easier to use and distribute: “I hope it doesn’t just stay in the lab.”

Backyard Remedies

Philip’s soil results returned to the red zone; With the exception of a pot plant, the location is contaminated with lead levels between 736 and 1196 ppm. Of course he is upset. “I had feared the levels of lead would be high,” he said, “but I didn’t anticipate them being that high.” He and his wife bought their house last year, so for them and many others moving out is not really an option.

Parents should check their children when they play in the backyard to ensure that they keep their hands out of their mouth and consider building a sandbox where they can play.

Gardeners can use raised beds with clean soil. Although plants generally don’t take much of lead – they tend to get stuck in the roots – you need to wash all vegetables in case a soil contaminated has blown onto them, and peel root vegetables. And try not to bring the dirt in your house. Philip stated that he and his wife would be certain to take off their shoes before they enter their home after working in the yard.

Landes thinks it’s unlikely that the state or city government will step in to help with the remediation. “So much of the Northeast is contaminated, I don’t see the government coming in and fixing everything.” However, she said, it helps to raise awareness and to know where kids should and should not be playing.

“Lead in the soil should probably be a concern for anyone who lives in New York,” she said. “You should get it tested before letting kids play in it, or before you plant a garden.”

Fortunately, they can take steps to protect their health, and they all come down to minimizing contact with contaminated soil.

If there is no budget to hire a professional lead abatement contractor, there are some options. Instead of digging the area to replace the soil, which could potentially put more lead into the air and in your home, the councils of Cornell University and the State Department of Health recommends New York to limit the contamination in place. Grass plants help keep the soil in place and mulch or gravel can cover it. Another option is to cover the soil with landscape fabric and add six inches of clean soil at the top.

None of this is easy work and it can be dangerous if not done right. Ideally you hire a professional lead abatement company like Eco Brooklyn. We always suggest getting the soil out of the garden, capping the area with landscape fabric and then bringing in new organic top soil.

Removing the soil usually involves bringing it through the house. This is where the biggest danger lies because the lead dust gets everywhere. It is important to build a plastic hallway that completely seals off the house. A fan is strategically placed to create a negative pressure. This ensures air flow moves from the house to the outside and not the other way around. Each day the area needs to be sealed off. The process is laborious but when it comes to the long term health of the family it isn’t worth taking any short cuts. The repercussions are just too high.