Bill McKibben, author of Eaarth and founder of 350.org, can either be seen as an optimist or a pessimist; it just depends which way you look at it. He can be an optimist because he believes the human race can survive climate change, but he is a pessimist because he believes that global warming will render the new “Eaarth” practically inhabitable.

In McKibben’s 2011 book “Eaarth” he presents a stark and sobering message about the world: we have waited too long to stop global climate change, and irreparable damage is not only unavoidable, but already underway. The planet that humans have developed on for tens of thousands of years is drastically changing into a planet that no human has ever experienced before. In McKibben’s eyes, this planet is so different that we might as well call it something else:“Eaarth”.

McKibben’s first and foremost goal is to convince you that global climate change is creating a new world; our old familiar globe is now heating, melting, drying, cooling, acidifying, flooding, and burning at an alarming rate. He believes that “the stability in which we have seen civilization develop has vanished; epic changes have begun”.

But with commitment and luck, we will be able to maintain a planet that will sustain some kind of civilization. Inherently, there will be a new type of planet, therefore we will have to create a new type of civilization. He offers the sobering advice that we as a society need to stop acting like teenagers learn how to “age gracefully”.

From an individual’s standpoint, global climate change is a complex problem to grasp and comprehend. If you may have noticed, in recent years, daily articles are constantly being published: a flood in Bangladesh, stronger tornadoes in the Midwest, a drought in Australia, extreme cold in Eastern Europe, and wildfires in Northern Canada- the list goes on.

These events seem like a travesty at first but they slowly slip from one’s mind if one is unaffected by such an event yet he points out that over weeks, months, and years, these isolated, seemingly unrelated events are becoming regular climactic occurrences to the point that these are no longer the exception.

They are the norm on planet Eaarth.

McKibben synthesizes these catastrophic weather occurrences, and by doing so he thoroughly convinces the reader that these are really catastrophic climactic occurrences. By compiling a series of unrelated weather events together the reader can see that these happenings are adding up to create a paradigm shift in our global climate system.

This is a powerful and sobering message: ongoing and drastic climate change is here to stay and it is happening a lot faster than we expected. McKibben pushes this point over and over again with example after example until the reader can only unequivocally agree with him.

But the catastrophic climate events that he describes are only half of the story- these events are causing a multitude of secondary problems: sea-level rise, proliferation of disease, extreme biodiversity loss, crop-yield destruction, ocean acidification, ice-cap melting, and permafrost thawing…he offers up many facts and figures to drive the point home.

If you did not think global climate change was upon us (or even real), after reading “Eaarth” there is no other way to think otherwise. McKiben’s Eaarth is the world we live in now. And this is just the first chapter of the book.

As the book proceeds into the next chapter, “High Tide”, McKibben switches his focus from the dire situation of the planet to the dire situation of our economics, and that our new planet requires new habits.

The world that society developed in was one where GROWTH was the mantra. Success and growth are synonymous in our society. But he argues that we have hit an economic and ecological wall because of the debt we have accumulated in both. We are no longer growing.

He begins by discounting the plans and projects that many environmentalists are dedicating their lives to – cap and trade programs, infrastructure changes, and behavior change campaigns.

Even though he supports these programs he doesn’t believe they will cause long-term change. He believes that there is nothing we can do to ward off the enormous change that is happening and already in full force; no political-socio-economic adjustments can change the direction of ecology at this point. McKibben’s point is that it is too little too late.

This is where I disagree. McKibben believes that the world has reached peak oil. But in recent years, new drilling techniques have been invented to continuously feed our oil-addicted economy. Methods such as deep water drilling, vertical drilling, and oil sands have continuously increased oil production. For the first time since the 1970’s, American oil production has increased due to new drilling practices implemented in North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Texas. As oil becomes scarce in easy places to drill, the risk becomes greater to obtain it – dozens of platforms are being constructed off of the coast of Brazil and research in the ANWR is being conducted by various oil companies.

In a recent Rolling Stone article, McKibben inadvertently refutes his opinions make in his book “Eaarth”. Last summer, the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a team of London financial analysts and environmentalists calculated the amount of proven coal and oil and gas reserves of the fossil-fuel companies, and the countries that act like fossil-fuel companies. In short, it’s the fossil fuel we’re currently planning to burn. The astonishing number: 2795 gigatons of carbon. The even more astonishing number: we have only burned 346 gigatons since 1751. We have not reached peak oil.

McKibben believes that growth will slow due to a crumbling global economy lacking oil. This is where our views differ. I believe (hope?) that we have not reached such a desperate state just yet. Some scientists estimate that humans can emit around 565 gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere by 2050 and still have some reasonable hope of staying below a two degrees Celsius warming.

But then, there are so many people with different agendas, it is hard to know who is telling the truth and who is manipulating the facts.

What is clear is throughout the book he paints a gruesome picture. The new Eaarth will be plagued by war, disease, natural disasters, and crumbling countries. He puts no faith in any political movement that has occurred in the past few decades. He believes that we must simply change the way we live.

We must alter the growth trends and establish “a condition of ecological and economic stability that is far into the future”. McKibben wants to strive for a world that is a quasi-utopia where each person can satisfy one another’s needs and have an equal opportunity to realize their true potential. It’s all a but vague.

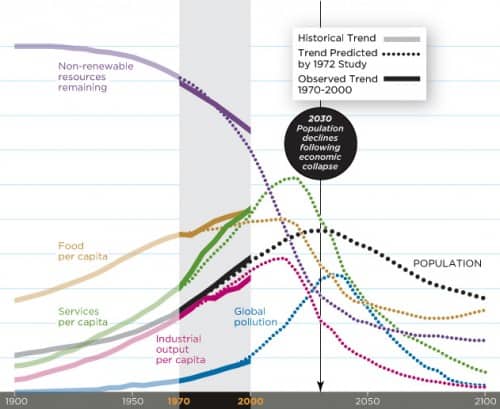

To further prove his point at this point in the book, he begins to discuss a paper that he bases the rest of his book on, called Limits to Growth by Graham Turner. The point to take away from this paper is that we are quickly approaching the limits of our climate, economy, and resources, which makes us susceptible to a collapse.

Whether this is graceful or a violent fall, he says, depends on how we manage our actions going forward.

For the rest of the book McKibben suggests that we should retreat to basics of human society where everything is local: the economy, food, relationships, and government.

He is essentially arguing for humans to regress back to the agrarian society that we lived in over 200 years ago. Also, at the end of this argument he offers to the reader a panacea for all of society’s problems after our decline: the increased utilization of the internet for decentralized information.

He offers up an example of what he thinks works: his small town in Vermont where everyone cooperates with one another and they are able to live sufficiently off arable land. I think his view is a little too Vermont-centric and American-centric. But is this really a practical solution for the rest of the world?

In 2008 for the first time in human history more humans live in urban areas than in towns or the countryside. Throughout the book, McKibben did not even mention the role of cities in developing a sustainable future. I think this is a mistake.

So what can we take from Bill McKibben’s manifesto? Regardless of all of the sobering points, there are actually a few key ideas that are extremely important to human survival in the age of “Eaarth”. The first point is that the “Eaarth” he describes is actually what has occurred to real “Earth” that we used to know and love. His message is blunt and truthful, instigating the reader to a more realistic view of our current reality, a reality you don’t see in mainstream media.

I believe that the rest of the points that McKibben makes are definitely tools that we can use to acclimate ourselves living in an era with an erratic climate. We should practice slow agriculture, continue to develop local economies, advance collective action within neighborhoods, and grasp a sense of who we are and where we came from. McKibben’s main points have a subtle sense of Thoreauvian philosophy- we should return back to the essential facts of life and discovering what we have lost along the way.

Ultimately point that “Eaarth” makes is that we need to get with the program. We no longer live on Earth – presumptions and habits that may have been ok before no longer apply, we can‘t presume Earth will have the same temperatures as the last year, we can‘t presumes crops will yield the same, and we can‘t continue acting like resources are limitless.

He offers many solid facts to back up his claims and he may not offer any solid solutions but in a sense Eaarth is the first step in an alcoholic’s twelve step program – you can’t deal with the problem until you actually admit you have one. After reading Eaarth it is abundantly clear we have a problem.

How we deal with it is not so clear.

Eco Brooklyn is focused on turning back the waste stream through radical salvage building and a deep commitment to creating buildings that offer more to the environment than they take away. We do this by building complex ecosystems that support more than humans – the green roofs, compost, gray water, ecological gardens, living walls, natural pools, and intelligent basophilic design all contribute to an environment that supports life.

We don’t have solutions for the planet but for our community, what we are doing seems to work. From that sense we are doing what McKibben is suggesting. His book was a great tool for us to see how our actions are aligning with other ecological pioneers, and we certainly see McKibben as a pioneer.